Alexander F. Gazmararian

Biography

Alexander F. Gazmararian is Assistant Professor at the University of Michigan, where he researches and teaches about the politics of climate change. His latest book is Climate Fault Lines.

He just launched the Climate Policy Workshop at the University of Michigan, an interdisciplinary space for faculty to workshop their social science research on climate change policy and politics.

If you're here for the AI Survey Defense Hackathon, go here to learn more.

Uncertain Futures

How to Unlock the Climate Impasse

Why is the world not moving fast enough to solve the climate crisis? Politics stand in the way, but experts hope that green investments, compensation, and retraining could unlock the impasse. However, these measures often lack credibility. Not only do communities fear these policies could be reversed, but they have seen promises broken before.

Uncertain Futures proposes solutions to make more credible promises that build support for the energy transition. It examines the perspectives of workers, communities, and companies, arguing that the climate impasse is best understood by viewing the problem from the ground up.

Featuring voices on the front lines such as a commissioner in Carbon County deciding whether to welcome wind, executives at energy companies searching for solutions, mayors and unions in Minnesota battling for local jobs, and fairgoers in coal country navigating their uncertain future, this book contends that making economic transitions work means making promises credible.

Awards & Recognition

-

Don K. Price Award - Best book on science, technology, and politics published in the last year (American Political Science Association, 2024)

-

Arnold Vedlitz Award - Seminal book on environmental issues published in the past two years (Southern Political Science Association, 2023)

-

Best Book on the Energy Market Economy (American Energy Society, 2023)

Press Coverage

Climate Fault Lines

The New Political Economy of a Warming World

Climate Fault Lines explores how climate change is affecting politics today and what our future holds in a warmer world. It places global warming's physical perils at the heart of climate politics, unlike theories focused on collective action or interest group resistance. The core claim is that climate change's unequal effects—a fault line cutting across existing social, economic, and political divides—will produce diverging political responses as the climate changes. People, businesses, and governments on the more vulnerable side of the fault line are most motivated to address climate change. This view departs from prevailing wisdom, such as the idea that Northern European states are climate leaders whereas developing nations are free riders. Above the fault line, when climate policy advances, it's not because these regions face the greatest danger, but because it delivers cleaner air, economic gains, or greater energy security, below the fault line, intensifying damage is what forces political action.

The book traces how these fault lines are emerging in domestic and international politics. It brings together models from geosciences and economics with diverse data on the public, businesses, cities, and countries. As warming accelerates, people and businesses with the most to lose are mobilizing, reshaping the incentives and policies of local and national governments. The result is growing divergence across the fault line. The world is not in the same boat: social harm, not shared vulnerability, increasingly shapes climate politics.

Articles

The Political Economy of the Clean Energy Transition

(with Dustin Tingley) Annual Review of Political Science. Forthcoming.Public Opinion Foundations of the Clean Energy Transition

(with Matto Mildenberger and Dustin Tingley) Environmental Politics. 2025. Forthcoming.Sources of Partisan Change: Evidence from the Shale Gas Shock in American Coal Country

The Journal of Politics. 2025.Press Coverage

Valuing the Future: Changing Time Horizons and Policy Preferences

Political Behavior. 2024.Press Coverage

Political Cleavages and Changing Exposure to Global Warming

(with Helen V. Milner) Comparative Political Studies. 2024.Fossil Fuel Communities Support Climate Policy Coupled With Just Transition Assistance

Energy Policy. 2024.Reimagining Net Metering: A Polycentric Model for Equitable Solar Adoption in the United States

(with Dustin Tingley) Energy Research & Social Science. 2024.

Working Papers

Experience and Self-Interest: Diverging Responses to Global Warming1/13/25

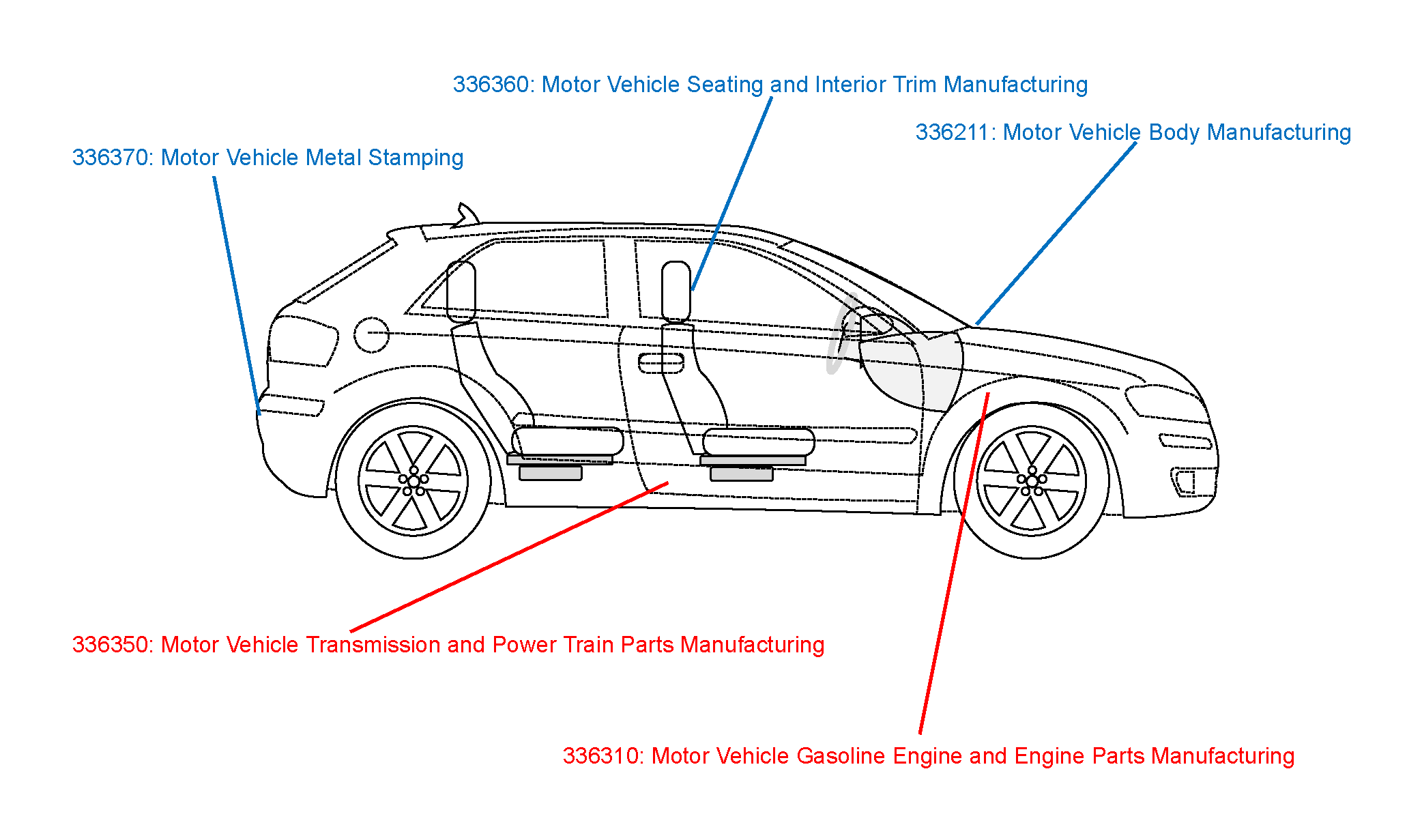

(with Helen V. Milner) Conditionally accepted at American Journal of Political ScienceDriving Labor Apart: Climate Policy Backlash in the American Auto Corridor8/23/24

(with Lewis Krashinsky)Press Coverage

Teaching

POLSCI 498: The Political Economy of Climate Change

Fall 2025. Undergraduate.Why is it challenging to stop climate change? The first half of the course examines global warming's political, economic, and societal consequences. The second half turns to the politics of solving the problem at local, national, and global scales. The readings weave together political science, economics, psychology, and philosophy. By the end, you should have a clearer understanding of why global warming is hard to solve and what we can do.

POLSCI 688: The Political Economy of Climate Change

Fall 2025. Graduate.This course reviews theoretical frameworks for understanding the political economy of climate change and explores new research on this topic.